Single revolution

The longest journey begins with a single revolution.

One factor in classifying the intensity of whitewater rapids is how easy or difficult it is to rescue yourself if something goes wrong. Class I is characterized by swift-moving water with a few, easily avoided obstructions. Any errors are easy to overcome with little consequence other than soaked stuff and wounded pride.

Class III and IV rapids, however, have different intensity and length and, for the more challenging Class IV, a more difficult rescue. It’s the difference, for instance, between the Ocoee with U.S. 64 running alongside it and the Chattooga, deep down a roadless wilderness gorge that is all but inaccessible. If you get hurt on the Chattooga, you and your companions are getting you to safety on your own power and by your own devices or you’re not coming out.

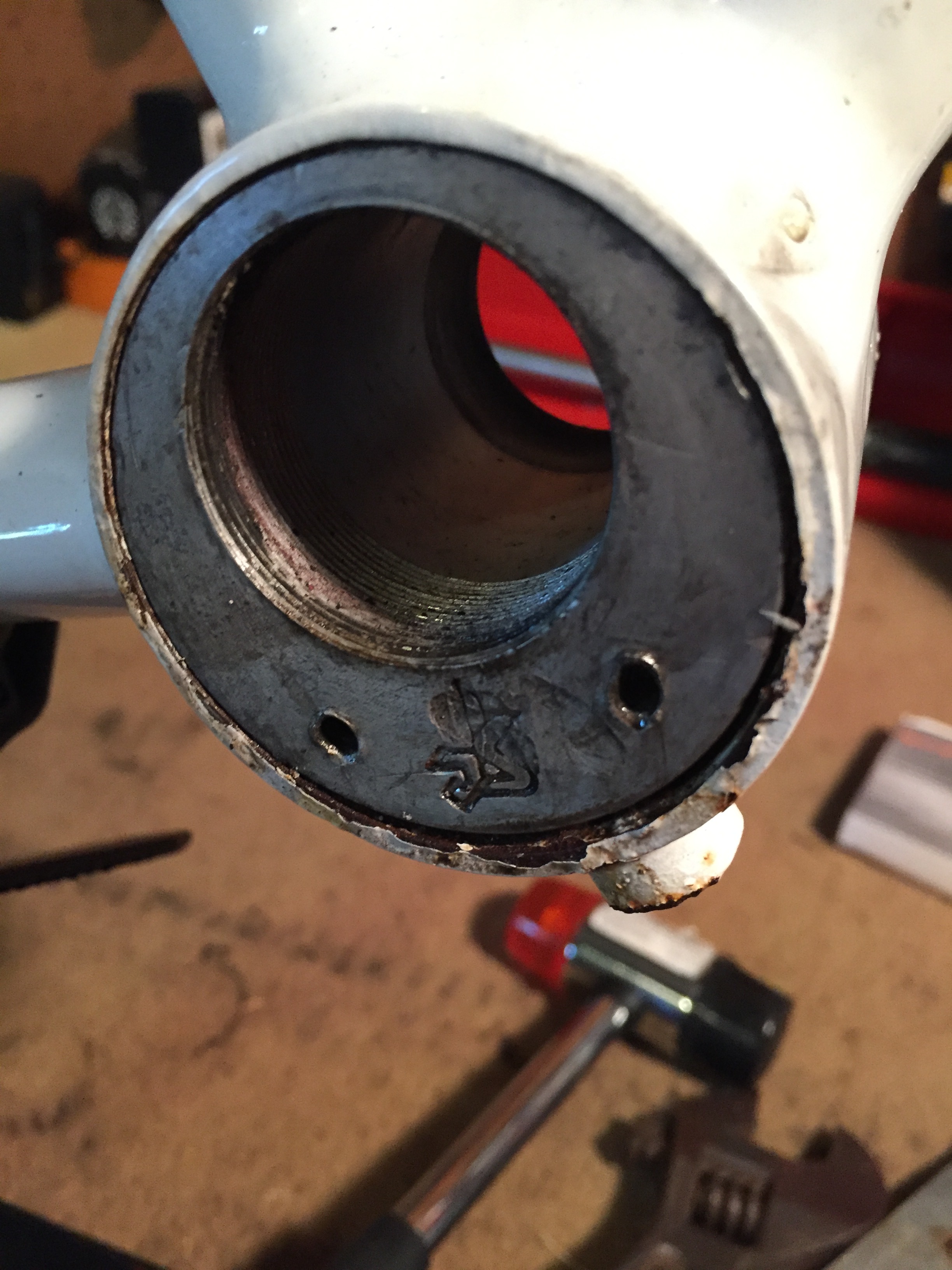

Circumstances are not so dire on this bicycle tour, and we’re staying in dry, soft beds after long, hot showers each night, but we will be without motorized SAG backup. Everything we’ll have for the week will be with us, carted around by our own power. When things go wrong –mechanically, meteorologically, muscularly – it’ll be on us to figure out how to overcome it. This may be as simple as powering through a long, hilly day with a headwind and a sore bum. It could be as inconsequential yet time-consuming as a blown tube and a broken spoke on a rear wheel. It might even involve a crash. Just a small one, mind you. No need to be alarmist. Maybe scrapes and a bent frame or bruised ribs and snapped cables.

The point is it won’t be a simple matter of radioing in the chopper for a live evac to the night’s lodging, as happened during a Day 1 thunderstorm in the 2017 version of father-son tandem adventuring.

No need to raise unwarranted concern. It just changes calculations. To return to a river analogy, the Class II Buffalo River is no danger at all on a June Saturday but becomes a life-endangering tumpus if the current pushes a canoeist into the frigid waters of a January morning. All it means is a smart person is prepared for conditions. Dry bags, plenty of warm clothes and the ability to start a roaring fire under pressure means the danger posed by a winter dunking far from help is much reduced.

The biggest thing we can do to assure success and overcome adversity and make it from Natchez to Tupelo all under our own steam is persist. The most meaningful thing we can do is refuse to quit.

The only thing for it is to pedal on.